Photo © Andrew Paul

By Andrew Paul

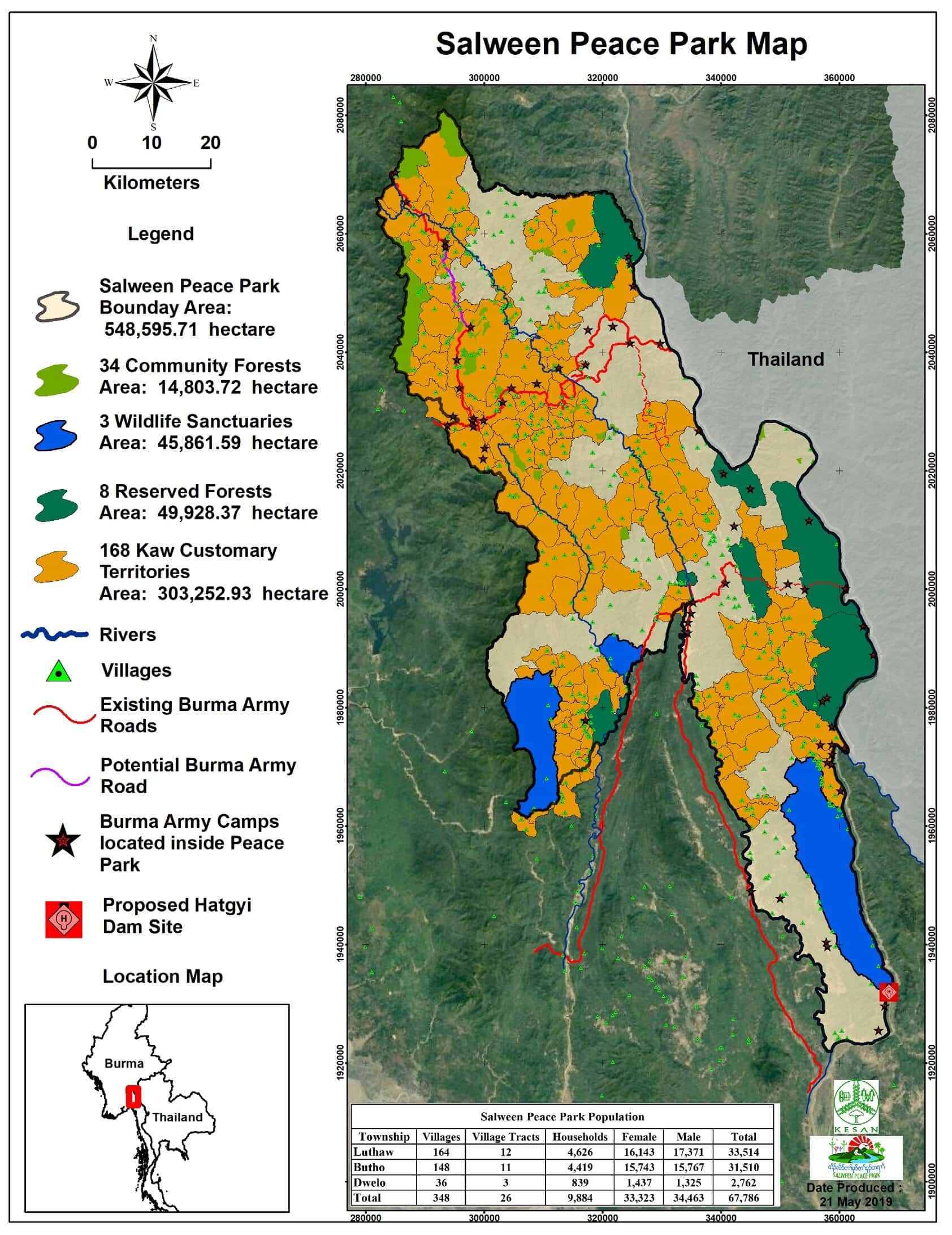

The Salween Peace Park is an Indigenous conservation area covering 5,485 square kilometres in the autonomous Karen territory of Kawthoolei, on the border between Thailand and Myanmar in Southeast Asia. Home to an estimated 70,000 villagers, the Salween Peace Park seeks to protect the land, uphold Karen cultural traditions, and articulate Karen villagers’ desires for peace in a place that has suffered more than 70 years of violent conflict between the Myanmar military and the Karen movement for self- determination led by the Karen National Union. All this in one of the most biodiverse regions in mainland Southeast Asia, where predators such as tigers and clouded leopards still stalk their prey.

Photo © Andrew Paul

My name is Andrew Paul. Before joining the IISAAK OLAM Foundation this year, I worked as a graduate student researcher and intern with the Karen Environmental and Social Action Network. I spent weeks at a time in the remote mountains of Kawthoolei, where villagers welcomed me into their thatch-roofed bamboo homes, several hours’ walk over steep mountain trails from the nearest road. Back in Canada, daydreams often take me back to Kawthoolei: boats on the river, peaceful villages, starlit nights, morning mists over the rice fields and bamboo groves, the call of a barking deer or gibbons in the forest. But most of all, I miss the people. I miss evenings with families around the hearth, a fire keeping evening chills at bay. I miss Karen home brew. And I miss talking into the night, as people shared their dreams – dreams for their children to have a better life, to live in peace, to protect their land. Dreams of the Salween Peace Park.

This week, I am travelling to Montréal to present on the Salween Peace Park at the Canadian Council forSoutheast Asia Studies. The theme of this year’s conference is “Power in Southeast Asia”. Power is an important theme in Indigenous conservation. Always the question is, how can Indigenous Peoples successfully defend their lands against the governments and corporations who covet these lands?

Photo © Andrew Paul

The Salween Peace Park tackles this dilemma by drawing on both internal and external sources of power. Internal power comes from strengthening Karen cultural and political traditions for community-based governance. The Karen customary land institution of Kaw, rooted in ancient ceremonies and spiritual protocols, constitutes the foundation for governance in the Salween Peace Park. Traditional rules protect sacred forest groves, fish pools, and streams. Taboos also prohibit hunting of tigers, gibbons, hornbills, and other species.

The people of Salween Peace Park have adapted traditional rules and added new ones to create the Salween Peace Park Charter, essentially a constitution for the park. Under the Charter, Peace Park governance is shared among village representatives, civil society, and the Karen National Union.

Thus, the Salween Peace Park’s strategy focuses on building internal power by strengthening local governance institutions. There has been no formal engagement with the Myanmar government, which remains hostile to Karen aspirations for self-determination. On the other hand, the Salween Peace Park draws on sources of external power (e.g., funding, technical capacity, political legitimacy) by engaging international conservation actors such as Wildlife Asia and the Rainforest Trust. However, no foreign organizations manage or control any projects in the park. The Karen people are clear: they invite outside organizations to support their efforts, but the Salween Peace Park will remain a Karen-led and Karen-controlled conservation initiative.

Saw O Moo (left) and Andrew Paul (right). Photo © Andrew Paul

The Karen have articulated their vision for peace – a vision that protects their lands and demands the removal of more than 60 occupying Myanmar military camps from the park. Villagers long to be free of this military occupation, which makes it impossible for them to return home to their lands and villages. Some villagers have been displaced from their villages for more than 40 years.

In 2018, in violation of existing ceasefire agreements, the Myanmar military attempted to force a tactical operations road through the heart of the Salween Peace Park. The Karen National Liberation Army fought back, and the fighting forced more than 3,000 Karen villagers to flee into hiding in the forest. Tragically, my friend and colleague Saw O Moo was ambushed and shot by Myanmar soldiers near his home. In the end, road construction was suspended, but sporadic clashes have continued throughout 2018 and 2019.

The fighting didn’t stop villagers and the KNU from declaring the Salween Peace Park on December 18, 2018. At the launch ceremony, leaders were presented with the Paul K. Feyeraband Award in honour of Saw O Moo and the Salween Peace Park’s efforts to build a “world of solidarity”.

In sum, the Salween Peace Park builds internal power by strengthening grassroots community governance, rooted in Karen cultural and political institutions. At the same time, the Karen draw on sources of external power as they build alliances with conservation organizations in their ongoing struggle against Burmese government and military domination.

This is the brilliance of Indigenous-led conservation; by drawing on multiple sources of power and legitimacy, these projects are much stronger than they would be if they either relied solely on external alliances, or else tried to ‘go it alone’ without any allies.

To learn more about the Salween Peace Park, please see the following series of videos:

The Salween Peace Park: A Place for All Living Things to Share Peacefully

Celebrating the Salween Peace Park Proclamation

Realizing Community Representation

The Nightmare Returns (account of fighting in 2018)

Saw O Moo: Defender of Indigenous Karen Territories

More resources on Salween Peace Park

Salween Peace Park Charter (briefer)

Salween Peace Park Charter (full document)

Salween Peace Park has been covered by international media outlets such as Al Jazeera, Mongabay, Reuters, and Intercontinental Cry, as well as outlets in Myanmar such as The Irrawaddy and Frontier Myanmar.

The Salween Peace Park is part of a large and growing global movement of “territories and areas conserved by Indigenous Peoples and local communities”, or ICCAs. To learn more, visit the ICCAConsortium website.